Every guitar player, at some point or another, aspires to own one of the top brand-name instruments on the market, whether made by Fender, Gibson, Gretsch, Paul Reed Smith or anyone else. In some ways, the guitar one plays becomes an identifying symbol; Stevie Ray Vaughn, for instance, was seldom seen with anything other than a Fender Stratocaster in his hands. Not many people could pick Peter Frampton out of a lineup today, but they know he played a Gibson Les Paul.

Every guitar player, at some point or another, aspires to own one of the top brand-name instruments on the market, whether made by Fender, Gibson, Gretsch, Paul Reed Smith or anyone else. In some ways, the guitar one plays becomes an identifying symbol; Stevie Ray Vaughn, for instance, was seldom seen with anything other than a Fender Stratocaster in his hands. Not many people could pick Peter Frampton out of a lineup today, but they know he played a Gibson Les Paul.

What about the rest of humanity, though, those of us who can’t afford to pony up $3,000 for a Gretsch White Falcon like Neil Young’s? What about the parents of a budding six-string prodigy who may or may not appreciate (much less learn to play) a Telecaster Deluxe? The well-known American guitar makers try to put affordable products on the shelves – Fender’s standard Strat sells for around a thousand dollars – but for beginner-budget players, the overseas market is the place where they can find the guitar to suit their needs, if not the guitar of their dreams.

For those who love that classic Fender sound, as so many people do, there are options. Fender offers a line of instruments manufactured in Mexico. An MIM designation does not denote an inferior instrument; it does take away that point of pride, affording their “gear-snob” friends a vantage point from which to look down. The differences are subtle enough that only seasoned players may notice – or care. The general belief is that Fender’s MIM line utilize multi-piece bodies (made of 3 to 5 pieces of wood), that the better necks are reserved for the American line, and that the pickups in the American guitars are slightly superior. The Mexican guitars also seem to have a thicker layer of paint and/or lacquer applied to them, possibly to cover up the multi-piece bodies, a factor which can “hug” the sound a little more closely to the guitar.

Japanese-made Fenders are considered a step up from the MIM line, and there are differences there too. For one, the saddles on the imported Fenders are spaced more narrowly than their American counterparts, a fact which can cause some confusion for do-it-yourselfers who have a proclivity for swapping out parts. The Japanese guitar factories also seem to be a bit fussier about things like the fret edges, and may have superior pickups than those supplied to the factories south of the border – but then, they’ve been doing it for a lot longer.

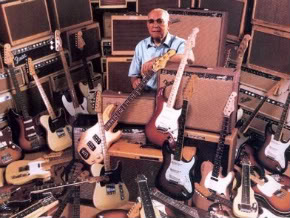

Japan has been producing guitars for decades, not only for their big-name customers like B.C. Rich, Ibanez and Fender, but on their own. The Japanese makers pour the quality into their work, with all manner of Yamaha, Teisco, Del Ray and other models still holding up against Father Time. What’s more, the Japanese models were made with a good deal of cultural flair, with their distinctive “tulip” body styles now sought after by collectors – this also applies to the guitars that were made in Japan for Harmony and others. The “surf sound” enjoyed by so many players is almost endemic to Japanese instruments, due to their near-universal utilization of single-coil pickups, including the vaunted P90.

Japan’s market share in the guitar world, however, has been usurped somewhat by their neighbors in South Korea. The Epiphone line, in particular, which produces affordable Gibson copies (in partnership with the parent company), is extremely popular among novices and professionals alike. The Epiphone Les Paul Ultra, for instance, features a set neck and alnico pickups – and bellows out sounds that tend to upset those who have paid three times more for their top-of-the-line Gibson.

The true benefit of an Epiphone guitar is that it allows a player to get the feel and tone of a fine instrument, such as a Gibson SG, that might otherwise be well beyond their resources. Paul Reed Smith is another maker that offers lower-cost Korean versions of their high-dollar guitars, which are attractive and push out some great sound, although those who have owned the premium PRS guitars would scoff at that notion. South Korean makers, like those in Japan, are also quite skilled at their craft – something that can only be attained through years of experience and strict quality standards.

Just as Korean makers have made inroads into Japan’s enterprise, many guitar makers have switched over to factories in Indonesia. Silvertone, the venerable brand that goes all the way back to the Sears-Roebuck catalog, has long been owned by Samick. Their Indonesian-made fare has carved a niche in the import industry. The Silvertone Rockit (an SG clone) and the Silvertone SSL3 (their version of the Les Paul) are quality instruments which draw favorable reviews from customers. They express near-disbelief that something with a $200 to $400 price tag could be so well-built, sturdy and playable.

Samick also has a line of guitars that are made in China. The Chinese have long been dogged by claims of counterfeiting and piracy, and it is true that many “fake” Fenders and Gibsons have been purchased online by unsuspecting consumers. The old adage, “If it sounds too good to be true, it probably is”, would apply to any purported American guitar in a lower price range. Advances in digital graphics, however, have made it possible for unscrupulous makers to produce copies of true classics that can easily pass the first-glance test, particularly if that first glance takes place via a computer monitor.

In all fairness, Chinese guitar makers have improved their craftsmanship, although their hardware and wood selections are still suspect. If you’re looking for a “cheap guitar“, then you might well be satisfied with a Gorham Tele-copy, which sells brand-new for as little as $80. The point there is that nobody is trying to pass off an inferior instrument as a high-quality American axe. Many guitar tinkerers may take some satisfaction, as well, in pulling apart their imports and replacing the pickups and the hardware with higher-grade substitutes in order to produce a guitar to their liking without spending a semester’s worth of tuition in the process.

In any event, it is a roll of the dice to purchase a guitar online, as the buyer cannot play or hear the instrument before it arrives on their doorstep. Sometimes the results can be perfectly satisfactory; other times it can be a truly regrettable experience – the latter being the underpinning of another old saying: “You get what you pay for.” When choosing an imported guitar off the rack at your local music store, no matter where it may have been manufactured, the best thing one can do is let the ears and the fingers make the final decision. As with beauty, what comprises a “good guitar” remains strictly the domain of the beholder.

Stick with a Japan or Korean guitar. You cannot go wrong.