By the final months of 1968, civil disorder in the United States was in full and bloody bloom. Against the backdrop of the Vietnam War, the country played out its own violent scenarios between the summers of 1967 and 1968, a period that saw race riots in Newark and Detroit, the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert Kennedy and the beating of protesters by Chicago police at the 1968 Democratic National Convention.

By the final months of 1968, civil disorder in the United States was in full and bloody bloom. Against the backdrop of the Vietnam War, the country played out its own violent scenarios between the summers of 1967 and 1968, a period that saw race riots in Newark and Detroit, the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert Kennedy and the beating of protesters by Chicago police at the 1968 Democratic National Convention.

Rock and Roll, at its heart a countercultural phenomenon, was uncharacteristically oblivious to these events. Apart from the Buffalo Springfield hit “For What It’s Worth,” the popular refrains of the day were largely wispy pleas to “try to love one another,” and assurances that “all you need is love.”

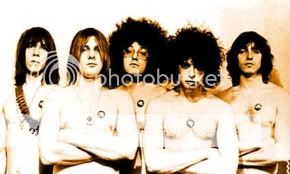

It was up to a group of Detroit rockers to shake rock from its dewy-eyed illusions. Formed in the city’s blue-collar suburb of Lincoln Park, the MC5—vocalist Rob Tyner, guitarists Wayne Kramer and Fred “Sonic” Smith, bassist Mike Davis and drummer Dennis Thompson—were a fledgling hard-rock band with a passion for Chuck Berry and modern jazz. The group had been together for two years when, in 1967, they placed themselves under the management of John Sinclair, Detroit’s legendary “King of the Hippies” and founder of the radical leftist White Panther Party. A former high school teacher, Sinclair preached an anti-establishment program designed to unseat authority through “rock and roll, dope and fucking in the streets.” In the MC5 he saw a tool to radicalize America’s youth; through Sinclair the MC5 saw a way to make the biggest rock and roll statement of all time.

“The times were very polarized—there was no middle ground for anybody,” says Wayne Kramer. “Music for us was a vehicle to express our ideas about how to change the situation and to articulate the frustration we felt at the slow pace of change.”

The forum for this mixture of politics and rock was the Grande Ballroom, and erstwhile big-band hall that by 1968 had become the hub of Detroit’s hear-rock scene. As the Grande’s house band, the MC5 played six nights a week, battering out tough, Neanderthal rhythms that, generously spiked with the influences of Sun Ra, John Coltrane and the demon weed, became potent avant-rock.

————————————————————

Few were unmoved by the nightly spectacle, least of all Elektra Records. No stranger to controversy (their biggest act was the Doors), the label signed up the MC5 with the radical idea of recording their first album in concert, a notion enthusicastically embraced by the group. “Playing live was our forte,” says Kramer. “But it was also much cheaper for Elektra to make a live record than a studio record. That was the attraction for them.”

A mobile unit was brought in, and on October 30, 1968, the MC5 cut Kick Out the Jams before a packed house at the Grande. While the band served up blistering performances of propagandist anthems like “Motor City Is Burning” and “Come Together” (it was their title before it was the Beatles’), the most inflammatory statement was screamed by Rob Tyner prior to the title cut: “Kick out the jams, motherfuckers!” If Electra wanted controversy, they would have it in spades.

“Electra said they would support us and leave that on the album,” says Kramer. “They believed in freedom of speech—until they discovered that there was gonna be so much heat coming down on them.”

It didn’t take long. Kick Out the Jams shot to No. 30 on the charts, but the glow of success was short-lived. Parents were outraged by the album, and the police started arresting store clerks who sold it. Even the feds got involved, alarmed by the group’s daring, in unfulfilled, manifesto to bring about change “by any means necessary.” Hoping to ease the record back into stores, Elektra replaced “motherfuckers” with the “brothers and sisters” delivery that had been recorded for the radio version of “Kick Out the Jams.” Sinclair’s seditious liner notes were likewise wiped away.

The revolution had been recalled. Soon after the record’s release, the MC5 and Elektra parted ways. The group drifted to Atlantic, where they recorded two albums of apolitical rock, neither of which sold as well as Kick Out the Jams. Sinclair was jailed for marijuana possession in 1971, and by the following year, the MC5’s members had scattered. Tyler died of a heart attack in 1991, and Fred Smith, who married poet and musician Patti Smith died of heart failure in 1994.

“The center never holds,” says Kramer, who resumed his recording career in 1995. “Nobody knew that, in the early Seventies, the war would wind down quickly and that pressure would come off the Civil Rights movement.”

The MC5’s legacy, however, did hold. By the mid-Seventies, New York rock acts like Television and the Ramones had claimed it for themselves, following witin a few years by bands in Britain’s punk movement. Says Kramer, “I thin if there’s one thing the punks picked up from us, it was our do-it-yourself ethic—that you don’t have to follow the program, and you don’t have to wait until society says it’s okay to do your thing. I think we showed it’s possible that you can even change the world.” Or at least the face of rock and roll.

Gear-Vault Classifieds is an eBay alternative. Come sell your used music equipment with us, for FREE!

Be the first to comment